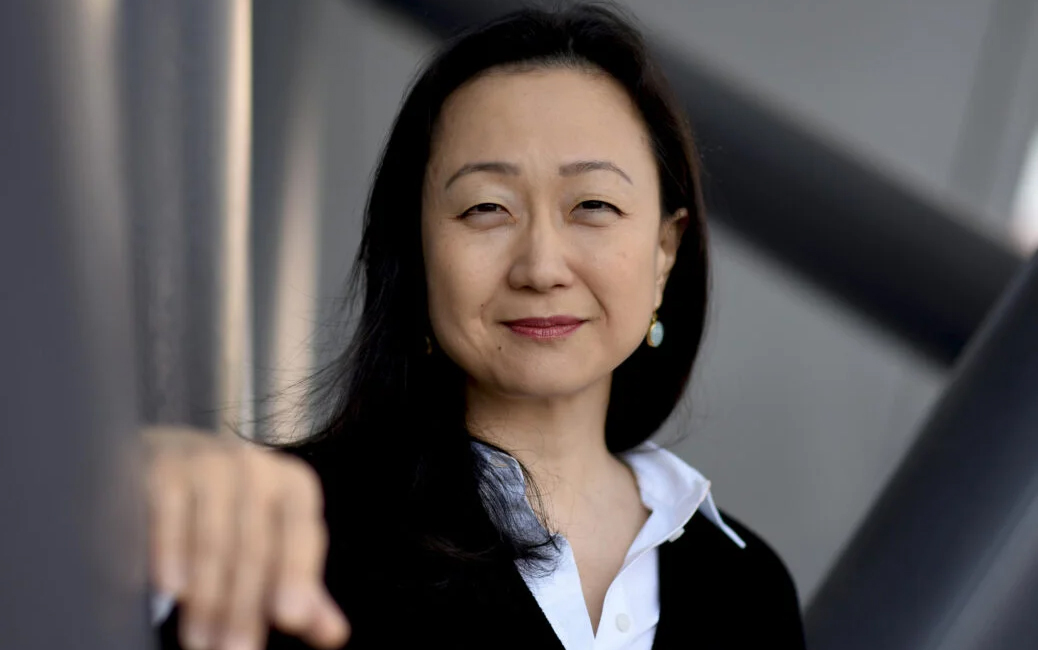

Author Min Jin Lee talks about her novel, ‘Free Food for Millionaires’

In some ways, author Min Jin Lee is exactly like Casey Han, the heroine of her novel, “Free Food for Millionaires.”

They’re both Korean immigrants who grew up in modest homes in Queens, a borough of New York City. Casey graduated from Princeton University; Ms. Lee, from Yale. But Casey, unlike Ms. Lee, is more like the alter ego of every good Korean-American girl — she talks back to her disapproving father, even though she knows she should treat him with respect. She skips law school. She smokes; she drinks; she dates white boys.

If anything, however, Ms. Lee, 40 years old, found her voice in Casey Han. She quit her job at a corporate law firm to write full time in 1995. Three unpublished novels and 12 years later, Ms. Lee finally had her breakthrough with “Free Food for Millionaires.” The book hit shelves in the U.S. in April 2007 and was favorably reviewed. The paperback edition is available in bookstores throughout Asia. It’s also been translated into Korean.

Ms. Lee, who lives in Tokyo with her husband and 11-year-old son, was in Hong Kong last month to attend the Man Hong Kong International Literary Festival. She spoke with Weekend Journal Asia about her successful literary debut.

Is “Free Food for Millionaires” autobiographical?

I think that I intentionally use autobiographical elements. I gave my character my height, my lipstick, the fact that I’m nearsighted and my neighborhood. Also the fact that I went to a very fancy college and I came from modest circumstances. Those are all absolutely intentionally put in there.

Having said that, my life has been so much less interesting than my character’s: I never smoked a cigarette; I got married when I was 24; I met my husband when I was 22, if you can believe that. There are just a lot of things I haven’t done that my character has done. But (they are) things that I wanted to do. Like I thought it would be really interesting to go to business school (as the character Casey Han does). I went to law school instead. I did a lot of the good-girl things that Casey would never have put up with.

Do you share the same perceptions about life as Casey?

In terms of perceptions and emotions, (she’s) absolutely autobiographical. I have felt all of those really embarrassing feelings. I have felt jealous. I have felt competitive. I have felt like a loser. I have felt like I have made some incredibly stupid choices. I have felt angry when I shouldn’t have felt angry.

I think those things that I was particularly ashamed of I decided to write about because this is my fourth novel manuscript, the first three having been rejected. So by this time I thought, “You know what, who cares? No one’s going to publish it anyway. No one’s going to read it. No one will ever interview me for The Wall Street Journal.” So all bets are off and I decided to use a lot of these very embarrassing feelings. I decided to write about sex. I decided to write about herpes because I figured nobody cares. I decided to write about physical violence within the Korean-American community — something that people don’t talk about — because I figured this book is really going to nourish me intellectually and I’m going to write it anyway and I’ve had all those rejections before, so whatever.

There’s a lot of freedom in failure and I can see that now.

In terms of the book’s Korean-American themes, were you trying to explore a lot of stereotypes?

It’s funny about the word “stereotype.” It usually means there is an existing type. For me, I didn’t see any (Korean-American) archetypes in literature or in media. These are people that I knew. So in order for me to write about it, it gave me these kinds of freedoms. I could talk about it.

Fiction is a very complicated baggy beast. Having said that, it’s a great place to put things in which you want to put your attention, especially things that are worthy of your attention. For me, whatever you write about should be worthy of your attention, worthy of your gifts. That’s very important.

Did you experience any kind of clashes of culture or wealth while living in Queens?

One of the things that was a big shock when I went to Yale (was) that I didn’t know about white people.

I didn’t think of anybody as white. I thought you are Puerto Rican or Jewish or Italian. Then when I went to Yale, there were white people. And I’m like, “What’s a white person?” That was a really big shock because usually it meant a WASP (white Anglo-Saxon Protestant) and a WASP didn’t mean white, it usually meant a ruling-class kind of white person.

So, like Casey, you started a big career and like Casey, you left that. What turned you away from that life?

I wanted other things in my life. Also I was very ill. I had this liver disease that I’ve had since I was a kid and it was getting worse. At one point I had liver sclerosis — I’m very well now — but it was a very important aspect to me because I didn’t want to die having lived this life. If I didn’t have that disease, I might have stayed a lawyer a lot longer. So if there’s freedom in failure, there’s also a kind of freedom in a kind of knowing that you’re mortal at an early age.

Do you resent or hold contempt at all for that world that you left?

Not at all. I don’t hold any contempt for people who are practicing law. I know how hard it is, I know how hard they work, and I know some of them who are so unhappy with it. As a matter of fact, a girlfriend of mine made partner at a law firm. I remember thinking: That’s unbelievable, what she did.

It’s a tremendous accomplishment. I don’t think I could have done what she did and I would never take away from her accomplishment. My parents taught me that. You really should respect other people’s work because work is hard-won.

This story originally appeared in The Wall Street Journal here.

Leave a Reply